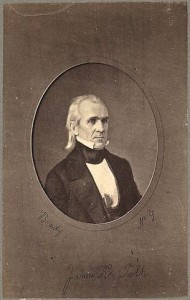

Library of Congress

Fulfilling a campaign promise, James K. Polk served only one term in the White House. But in domestic and foreign affairs—in ways that defined and shaped the years of his own public life and continue to weigh upon our age—he left a ubiquitous and, even now, contested legacy.

Born in North Carolina in 1795, Polk moved with his family to Tennessee while he was still a boy. There, as a young man, he began careers as a lawyer, planter, and politician. Eventually becoming a protégé of fellow Tennessean Andrew Jackson, Polk—later dubbed “Young Hickory” due to his relationship with “Old Hickory”—rose quickly in state and federal politics. He served as a member of the state legislature; as a member of, and Speaker of, the U.S. House of Representatives; and as Tennessee governor. In 1844 Polk became the unexpected Democratic nominee for president, a feat widely believed to have occasioned the first usage of the term “dark horse” candidate.

In the November 1844 general election, Polk defeated Whig party nominee Henry Clay. In March 1845, when Polk took the oath of office, he became, at forty-nine, the youngest man to that time to have assumed the American presidency. He soon moved to resolve longstanding tensions with the United Kingdom over rival claims on the Oregon Country, a realm extending north into today’s British Columbia and south encompassing the modern states of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho and the western portions of Wyoming and Montana. Ultimately, rebuffing strident calls for war from the expansionist wing of his own Democratic party, Polk struck a compromise with London. He agreed to divide the contested Oregon Country mostly along the 49th parallel, which forms today’s U.S.-Canada border.

Polk’s desire for U.S. acquisition of Texas, New Mexico, and California proved more difficult to consummate. Anglo settlers in Texas, rebelling in 1836, had transformed that Mexican province into a nominally independent republic. Mexico, however, had refused to recognize the secession. The lame-duck president John Tyler, in April 1841, entered office as a Whig but soon became estranged from that party. He interpreted Polk’s November 1844 election to the presidency as a mandate to grant Texas’s desire for U.S. annexation. So, in early 1845, before Polk took office, Tyler engineered the passage of a joint resolution by the U.S. Congress that offered Texas immediate statehood. Texas accepted the offer. In July 1845, with Polk’s signature, a bill granting statehood became federal law. These actions of Tyler and Polk exacerbated already-troubled U.S.-Mexico relations. By spring 1846, under President Polk, war raged between the two nations. In 1848, under the terms of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed that February, Texas, New Mexico, and California all came under uncontested U.S. dominion.

In addition to Texas, the Oregon Country, Mexico, and other well-known concerns of Polk’s presidency, the series’ recent and forthcoming volumes include letters documenting numerous historiographically neglected foreign policy initiatives of his administration. Among these are Polk’s unsuccessful attempts to place Cuba under U.S. dominion; his efforts to negotiate treaties with the German Customs Union and the Kingdom of Hawaii; his response to calls for U.S. relief for victims of the Irish potato famine; and his contemplated military intervention in Yucatán, a putatively independent and neutral state during the Mexican-American War that was enmeshed in violence between Hispanics and Indians.

Other topics addressed in these final volumes include the president’s ongoing patronage woes and other intra-party rivalries; his preoccupation with the political affiliations of candidates for appointments to military commands; and his untiring efforts to tamp down both Whig and Democratic congressional opposition to the war with Mexico. The letters also document Polk’s thoughts on the 1848 presidential race and his efforts to advance the candidacy of Democrat Lewis Cass in that contest. Over everything hovered the specter of slavery, an increasingly controversial institution that endangered several of Polk’s initiatives and threatened civil war.